Cinema has long been a medium that challenges and confronts people, with Australia being a healthy contributor in this regard. The most recent example to emerge from the Antipodes seeks to examine the country’s colonial past, doing so in a brutal manner that borders on unwatchable.

Cinema has long been a medium that challenges and confronts people, with Australia being a healthy contributor in this regard. The most recent example to emerge from the Antipodes seeks to examine the country’s colonial past, doing so in a brutal manner that borders on unwatchable.

Sometime during the 19th century, Irishwoman Clare Carroll (Aisling Franciosi) is living in the British colony of Van Diemen’s Land with her husband Aiden (Michael Sheasby) and newborn child. Being female, Irish and a former convict, Clare is perpetually faced with adversity, whether that be from the maid who employs her, the corrupt Army officers hired to keep the peace, or the hostile wilderness that surrounds them all.

One evening, three of the aforementioned officers take advantage of Clare’s situation by forcing their way into the Carrolls’ makeshift house, sexually assaulting her and knocking her unconscious. Clare awakes from the horrific experience next morning to find her husband and baby killed, leaving her devastated and wanting revenge. For that to happen, Clare must follow the three men to Launceston, where they are poised to receive a promotion for their work.

The Nightingale is the second feature-length film of Australian director Jennifer Kent, who five years ago enjoyed huge critical success with The Babadook. Kent’s debut feature has been heralded as an exemplar of horror done properly, with many believing her efforts would assist in revitalising or even revolutionising the genre. That isn’t the case with The Nightingale, but only because the picture is closer in tone to a thriller. Or an historical drama. Or a Western.

Although it’s set in the lush fernery and tall forests of Tasmania, there’s more than a hint of the Old West present in The Nightingale – it has white characters trying to conquer a wild frontier, adversaries in the form of crooked authority figures, people riding on horseback, guns being shot, and natives who help the protagonist on their quest. Having these tropes placed over a beautiful green backdrop is somewhat jarring initially, yet ceases to be a distraction as the film continues.

Kent’s picture is not the first “Western” to be filmed in Australia, nor the first to be set prior to Federation, but The Nightingale is a pioneer in another regard. Whereas other films about the colonial era have male leads, here the central protagonist is female, which allows the story to offer a side of history rarely seen in the medium. As The Nightingale contends, women faced immense hardship during early settlement of Australia, subject to chauvinistic behaviour and squalid working conditions.

-

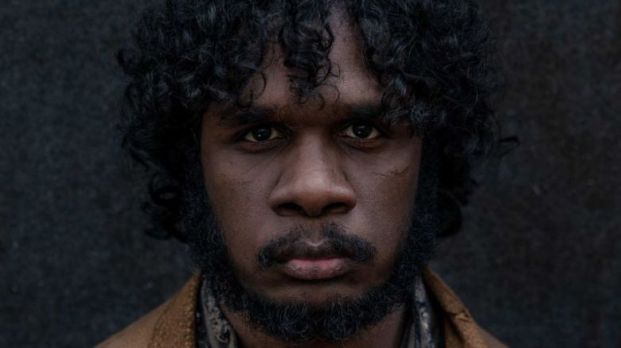

Mangana (Baykali Ganambarr) as he appears in The Nightingale

Not content with its feminist undertones, The Nightingale is doubly progressive for being a tale about the Indigenous experience under British rule; this is conveyed through the character of Mangana (Baykali Ganambarr), an Aborigine who Clare hires to track the antagonists. Mangana’s life is one of exploitation, fear and loss, having been removed of his family, home and even his name – to the whites, he is known only as “Billy”. His story is typical of what Indigenous Australians suffered during the colonial period.

Kent is to be admired for handling such material, but original her efforts are not – films such as Fred Schepisi’s The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith and more recently, Warwick Thornton’s Sweet Country have also examined the Indigenous experience through the prism of the Western, only with more grace and restraint. The Nightingale offers no such caution, defiantly being a no-holds-barred, uncensored account of what Aborigines were subject to at the hands of the colonists.

The direction of Kent is nothing short of bold, which is ultimately The Nightingale’s greatest undoing. Within minutes of the film beginning, viewers are met with gratuitous, prolonged sequences of sexual assault, graphic violence and child abuse, each being more senseless and pointless than the last. The problem is not so much the explicitness of these scenes as it is their excess – by the fifth or sixth instance of inhumanity, there is no emotional impact to be felt.

What’s most frustrating about these moments of depravity is that no justification is made for their inclusion. To display one scene of rape would be sufficient, while two can be tolerated; but to show three or more of these sequences is pointless – the viewer has nothing to gain by witnessing such behaviour on multiple occasions. Worse still, these actions craft an incessantly bleak atmosphere that gives the characters no hope of redemption, a feeling that lingers as the credits roll.

Jennifer Kent’s The Nightingale is something to be admired and abhorred in equal measure. Qualities such as picturesque scenery and a female protagonist are marred by a directorial style that is undoubtedly fearless, yet also mortifying. Only those with the strongest of stomachs need bear witness to it.